Nvidia, AMD, Amkor, Arista @ UBS Tech Conference

XPU vs GPU longevity and replacement cycles. Arista's AI opportunities & Broadcom. Amkor Arizona & TSMC.

Thoughts from various conversations at the UBS conference last week:

Nvidia

No Replacement Cycles Yet

Colette confirmed that there hasn’t been a datacenter GPU replacement cycle yet:

Timothy Arcuri: And I get the question a lot about how much of what you’re shipping is replacing existing GPUs versus just additive to the existing base. And it seems like almost all of what you’re shipping is just additive to the base. We haven’t even begun to replace the existing installed base. Is that correct?

Colette Kress: It’s true. It’s true that most of the installed base still stays there. And what we are seeing is the advanced new models want to go to the latest generation because a lot of our codesign was working with the researchers of all of these companies to help understand what they’re going to need for their next models. So that’s the important part that they do. They move that model to the newest architecture and stay with the existing. So yes, to this date, most of what you’re seeing is all brand new builds throughout the U.S. and across the world.

On the one hand this is fairly obvious: GPUs, even older ones, are super useful whether you’re pre-training, post-training, fine-tuning, serving inference, labeling data, simulating autonomy, synthetic data generation, ablation studies, regression testing, etc etc. R&D teams everywhere can absorb essentially unlimited amounts of old GPU compute. Every lab has more experiments it wants to run than budget for new GPUs.

So why throw out old GPUs that can still crank out tokens, even if the throughput is lower? Especially if they are nearly or fully depreciated!

But it does raise the question: what would cause GPU replacement cycles?

Power Budget Reallocation

Recall that power is a constraint. Remember how Andy Jassy answered a capacity question on the Amazon earnings call in terms of power and not chips?

Justin Post: I’ll ask on AWS. Can you just kind of go through how you’re feeling about your capacity levels and how capacity constrained you are right now?

Andrew Jassy: On the capacity side, we brought in quite a bit of capacity, as I mentioned in my opening comments, 3.8 gigawatts of capacity in the last year with another gigawatt plus coming in the fourth quarter and we expect to double our overall capacity by the end of 2027. So we’re bringing in quite a bit of capacity today, overall in the industry, maybe the bottleneck is power. I think at some point, it may move to chips, but we’re bringing in quite a bit of capacity. And as fast as we’re bringing in right now, we are monetizing it.

Could we see a scenario where older GPUs get unplugged to free up the power for the latest generation chips that produce more tokens per Watt?

Put succinctly: might power budget reallocation drive a replacement cycle?

If this does happen… hyperscalers, PLEASE donate those old chips to academia! I did my graduate nanoelectronics fabrication research using old tools donated from industry. We could do the same industry to academia recycling for AI compute.

This topic makes me wonder — what is Google doing with old TPUs? We’re on v7 now…

What’s the useful lifetime of those?

If Google isn’t using all of the oldest ones… what happened to them?

And if they ARE still using them, that would be very interesting to know.

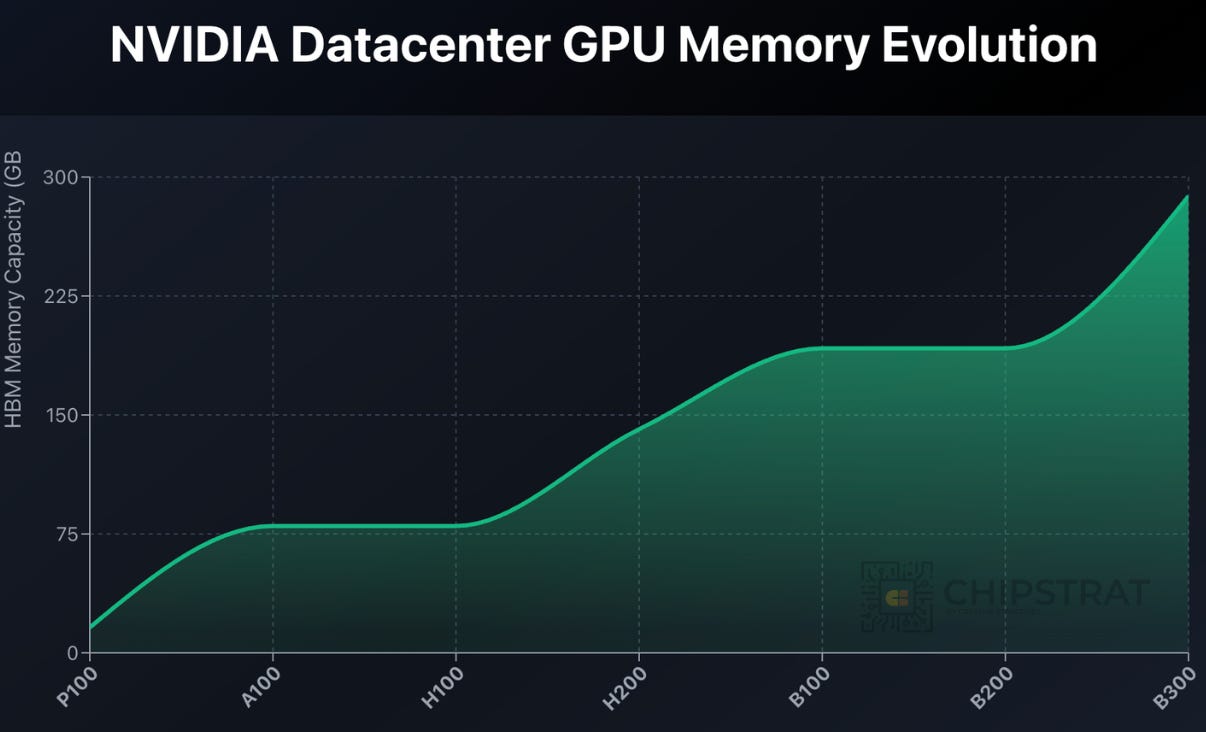

Not Enough Memory

Legacy GPUs have smaller HBM capacity and bandwidth. Yet models continue to expect bigger context windows, etc.

Could memory, not compute, become a limit?

Think of this like older smartphones that eventually fail to run modern apps because the memory budget no longer matches the software expectations.

Similarly, the GPUs can still crunch matmuls, but they’ll struggle to hold the entire working dataset in memory which forces offloading and kills useful throughput.

Thus, the breadth of “other useful jobs” such GPUs can still help with would narrow over time. Decode-only workloads. R&D tasks that don’t need a ton of memory. Etc.

Hyperscaler XPU Competition

Timothy Arcuri: Let’s talk about competition. So we haven’t even seen a model yet trained on Blackwell. So everyone is a little up in arms about whether your competitive lead is shrinking or not. So maybe you can speak to that.

Colette Kress: Yes. So let’s just talk about where we stand. We’re very excited in terms of our Grace Blackwell configurations that we put in the market. That’s both the 200 series as well as the Ultra Series and the 300.

Today, you’re going to continue to see more and more models coming into the world. Those models are right now being built, and you’re probably going to see them in about 6 months coming out in terms of the new models.

What we did and when we created our Grace Blackwell configuration, that was an important change that we made in terms of completing full data center scale. We refer to that often in terms of rack scale. But I think the important part to remember that, that, that was a focus in terms of extreme co-design that would be necessary, not with just 1 chip, but 7 different chips altogether working to create what is going to be very important for both accelerated computing and many of these new models that would be coming to market. So we’re very pleased with that. But keep in mind, it’s just not related or is not anything similar to what you may see in a fixed function ASIC. It’s very, very, very different. So today, everybody is on our platform. All models are on our platform, both in the cloud as well as on-premise. All workloads all continue to be on our platform.

Summing up Kress,

Grace Blackwell was the first “rack scale” architecture, with extreme co-design across GPU, CPU, and networking

Models trained with said rack-scale architecture haven’t hit the market yet

This is different than “fixed function ASICs”

Definitely agree that GB is the first merchant vendor rack-scale architecture. Beat AMD to that one by a lot.

I’m interpreting the “fixed function ASIC” as a reference to hyperscaler XPUs, i.e. Google TPUs and Amazon Trainium.

I’m not sure what Kress meant by “it’s not similar to what you see in a fixed function ASIC”. I think, at the chip level and the system level, there are a lot of similarities between XPUs and GPUs, although clearly the companies behind them are designing for different objectives.

AWS’ Trainium3 is a good example. SemiAnalysis has an excellent breakdown of the chip and the rack-scale system around it.

First, Trainium3 is not “fixed function”; it is a programmable accelerator with architectural choices tuned for GenAI. For example, SemiAnalysis notes that Trainium3 doubled MXFP8 throughput while keeping BF16 unchanged, a deliberate tradeoff because Anthropic can manage training in FP8. Still programmable, just different design decisions.

Pedantically, “domain-specific accelerator” is the accurate label for Trainium, not “fixed function ASIC”.

A charitable read of Kress’ “fixed function ASIC” is that she just used it as shorthand for “a chip with less flexibility than a GPU”.

Secondly, the SemiAnalysis article makes it clear that the Trainium team did co-design the system at rack scale, again around different goals than a merchant silicon vendor. AWS optimized for “fastest time to market at the lowest TCO”. That makes sense for a company with a cloud computing business. On the other hand, Nvidia designs for absolute peak system performance, which makes sense for a merchant silicon vendor. The business models drive different architectural choices.

So AWS makes different choices than Nvidia’s GB systems, like:

Air-cooled racks to avoid facility redesigns and preserve datacenter fungibility.

PCIe6 now and UALink later to start deployments immediately while keeping an upgrade path.

Cableless trays with retimers to simplify manufacturing and integration.

Lots of similarities between GPUs and XPU, but also many important differences.

As driven by the business models.

AMD

Hyperscaler XPU Competition

Lisa’s framing of XPUs was a bit more on the nose:

Timothy Arcuri: So there’s been some recent news in the market that have made people think that ASICs are going to take over the accelerator market. And I just wanted to get your opinion on that and sort of the general competitive landscape in the AI world. Are ASICs really a threat to GPUs? You’ve said that ASICs will have a 20%-25% share of the market. Has anything we’ve heard recently changed your view on that?

Lisa Su: I actually don’t think so. I think what we have said about the market is what I started with, which is, the market wants the right technology for the right workload. And that is a combination of CPUs, GPUs, ASICs and other devices. As we look at how these workloads evolve, we do see some cases where ASICs can be very valuable. I have to say that Google has done a great job with the TPU architecture over the last number of years. But it is a, let’s call it, a more purpose-built architecture.

Yes. Good answer. Trainium3 is purpose-built for GenAI. This is better than “fixed function ASIC”.

Lisa Su: It’s not built with the same programmability, the same model flexibility, the same capabilities to do training and inference that GPUs are. GPUs have the beauty that they are a highly parallel architecture, but they’re also highly programmable. And so they really allow you to innovate at an extremely fast pace.

Well… all of this is very true about GPUs. But when you dig into SemiAnalysis’ look at Trainium 3, we see a highly parallel architecture and that’s highly programmable too. In each of the Neuron Cores,

The Tensor Engine is a 128x128 BF16 Systolic Array and a 512x128 MXFP8/MXFP4 Systolic Array. The BF16 Systolic array size on Trainium3 is the same as Trn2’s BF16 array size but on FP8, it is double in size.

Very parallel architecture.

And regarding software,

On the software front, AWS’s North Star expands and opens their software stack to target the masses…. In fact, they are conducting a massive, multi-phase shift in software strategy. Phase 1 is releasing and open sourcing a new native PyTorch backend. They will also be open sourcing the compiler for their kernel language called “NKI” (Neuron Kernal Interface) and their kernel and communication libraries matmul and ML ops (analogous to NCCL, cuBLAS, cuDNN, Aten Ops). Phase 2 consists of open sourcing their XLA graph compiler and JAX software stack.

By open sourcing most of their software stack, AWS will help broaden adoption and kick-start an open developer ecosystem.

Programmable. Wasn’t user-friendly, but embracing open source and working to get better. Sounds like ROCm in that sense!

But pardon my interruption, let’s let Lisa continue:

Lisa Su: So when we look at the market, we’ve said that we see a place for all of these accelerators.But our view is, as we go forward, especially over the next, let’s call it, 5 years or so, that we’ll see GPUs still be the significant majority of the market because we are still so early in the cycle and because software developers actually want the flexibility to innovate on different algorithms. And with that, you’re not going to know a priori what to put in your ASIC. So I think that’s a difference.

Won’t know a priori what the future algorithms will need in the AI accelerator.

That gets at the heart of it.

XPUs make deliberate precision choices that optimize for today’s workloads but narrow future flexibility. For both production and R&D workloads.

As we saw, Trn3 is MXFP8-centric. Yet GPUs keep improving many precisions in parallel (FP8, FP6, and FP4). This leaves headroom for new model types and experimental architectures that may not fit neatly into an MXFP8-centric design.

And as we saw with memory capacity, these point-in-time design decisions can limit the breadth of reuse.

GPU flexibility creates a long reuse tail because older GPUs remain useful for fine-tuning, inference, simulations, and new research ideas long after depreciation.

XPU specialization can shorten that lifecycle. Future production algorithms may fall outside the precision regime the silicon was built around, and many non-production R&D workloads may also depend on precisions or kernel variants that the XPU cannot support efficiently.

GPUs being more flexible is well understood, but the sharper point here is about productive lifetimes. The productive lifespan of an XPU may be shorter because its architectural trade-offs are tied to a specific point in model evolution. Those choices boost efficiency/TCO/time-to-market today but may constrain how well the hardware maps to tomorrow’s production and R&D workloads.

Again, would love to get some insights and rebuttals from the Google TPU team here!

Arista & Amkor

Although it feels like many companies have already seen their growth trajectory due to AI, both Arista and Amkor believe their uplift is still ahead of them. I haven’t covered them in depth yet, but will do so soon.

At UBS, those growth vectors were discussed.

Arista: scale-out Ethernet, scale-up Ethernet, riding Broadcom’s XPU coattails

Amkor: American advanced packaging! Also interesting discussion addressing competition from TSMC’s Arizona advanced packaging.

Let’s jump in. The first 50% of the article was free, the rest is for paid subs. Appreciate y’all!